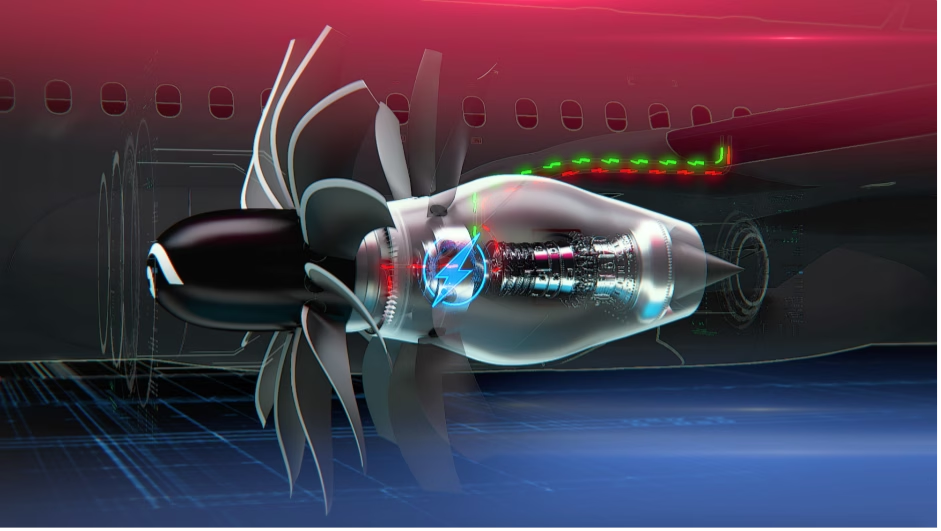

The next generation of flying might look very different. General Electric and Safran have previously unveiled a new engine design. Now, Singapore is preparing to become the first location worldwide to test open fan engines at operational airports. Engineers call it the Open Fan engine. This bold architecture is part of the CFM RISE program. It aims to cut fuel use and emissions without sacrificing speed.

The Big Change: No More Casing

The missing nacelle defines the new GE Open Fan engine. You see this metal covering on every standard jet engine today. The design removes this heavy weight. This allows engineers to use much larger fan blades.

These massive blades measure over 12 feet across. They pull in much more air than a standard jet. This improves how the engine turns fuel into movement. The result is a big leap in performance.

20 Percent Fuel Savings

Aviation experts view this program as a major step for the planet. The Open Fan engine aims for a 20 percent reduction in fuel use and CO2 emissions. It compares well against the most efficient engines flying today.

The industry usually fights for small gains. A 20 percent jump is huge. This efficiency could help airlines meet strict environmental goals in the coming decades.

It Is Not Just a Propeller

Some observers mistake the exposed blades for a traditional propeller. But the technology differs greatly. This engine cruises at Mach 0.8. That is the exact same speed as a Boeing 737 or Airbus A320. Airlines will not need longer flight times to save fuel.

Engineers also solved the noise problem. Older unducted engines from the 1980s were loud. This new design uses supercomputers and stationary vanes to smooth the airflow. It targets the same noise standards as current turbofans.

Ready for the Future

GE built the Open Fan engine with versatility in mind. It works with 100 percent Sustainable Aviation Fuel. It also runs on liquid hydrogen and hybrid electric systems.

GE has already started flight testing, and organizations are beginning to demonstrate the program. If the program meets its goals, this open-rotor design could power new planes by the mid-2030s. The design is radical, but the goal is practical efficiency.